We go for the next generation. We go for progress. We go for a greater understanding of the universe. We go to prove that getting to Mars is possible by using today’s technology. We go forward to the Moon now for her first steps. We go for all of us, here on Earth.

For more than 60 years, space exploration has been our driving force at Lockheed Martin. In our high bays, labs and advanced technology centers, we created an engine of innovation that continues to push for – and make possible – the permanent expansion of humanity into our solar system and beyond.

At Lockheed Martin, we go for the greatest adventure in human history.

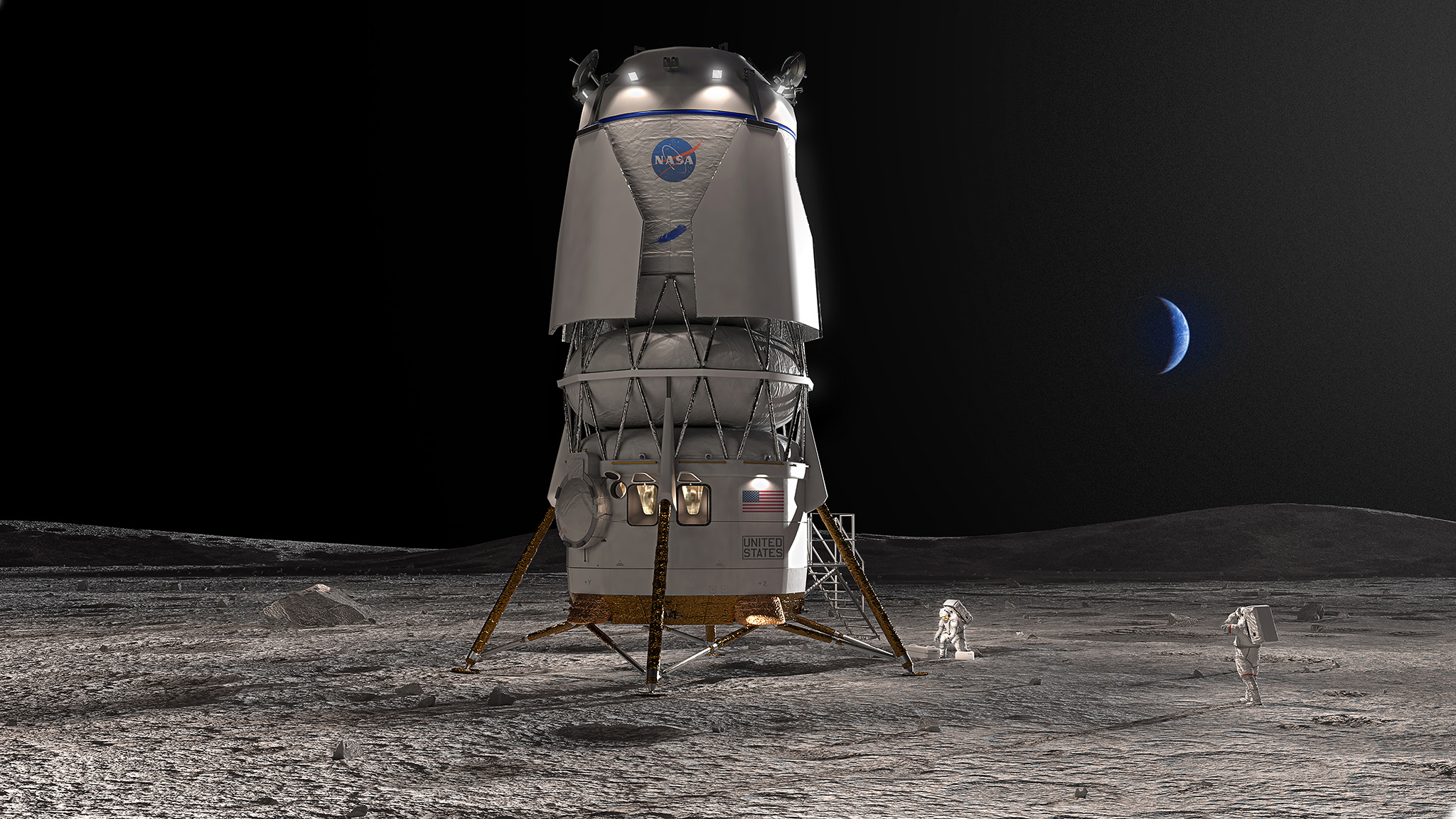

NASA’s Orion spacecraft, designed and built by our engineers, stands as a pivotal asset for human deep space exploration due to its robust design and capabilities. Serving as the crew vehicle for NASA’s Artemis program, Orion is integral to humanity’s return to the Moon, marking the first step in a renewed era of lunar and deep space exploration.

Orion’s significance extends beyond lunar missions, as it is envisioned as a key component for eventual crewed missions to Mars. With deep space navigation capabilities, life support systems, radiation shielding and a lunar velocity heat shield, the spacecraft is positioned as a pivotal element in the ambitious pursuit of sending humans not only to the Moon, but to the Martian surface. In essence, Orion plays a critical role in paving the way for humanity’s expansion into the far reaches of space.

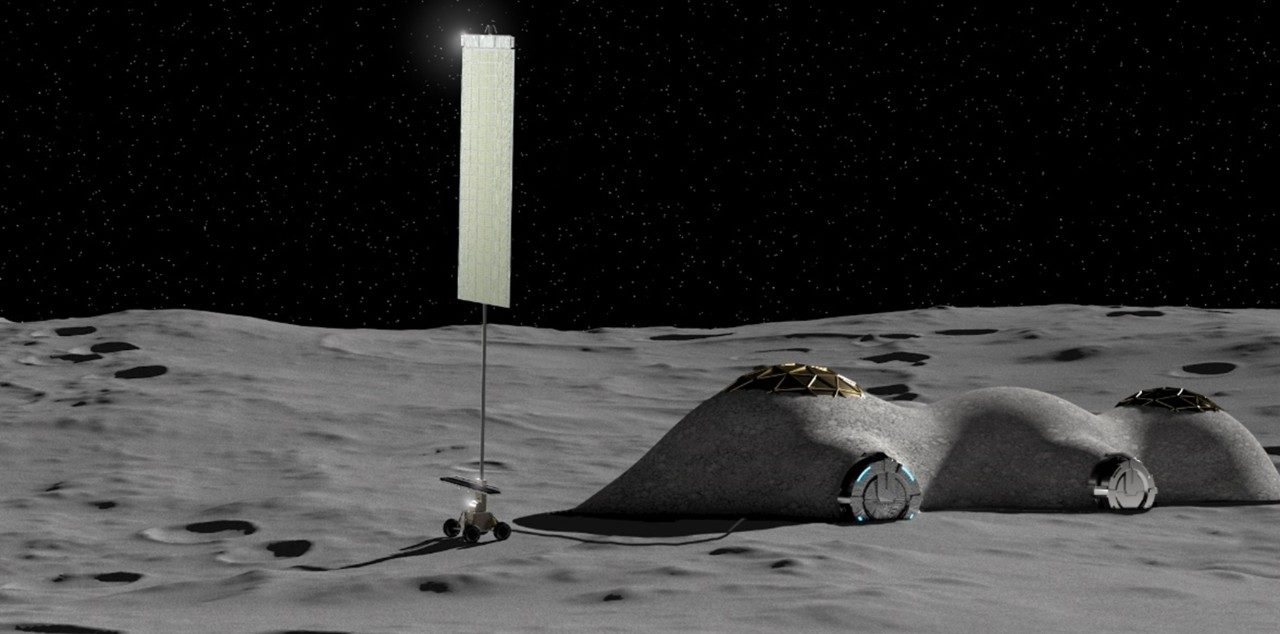

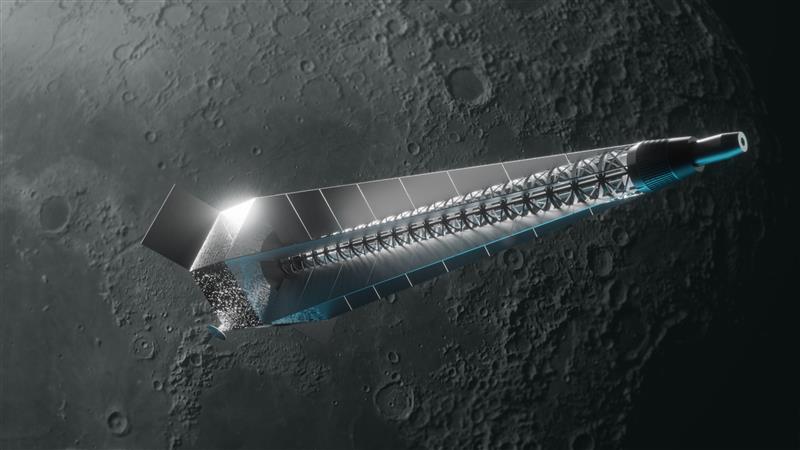

Science fiction is becoming reality: we are going to the Moon and Mars. Since the days of the Apollo program, Artemis is taking what we’ve learned from those missions to go beyond — landing on the Moon but also building a presence there that eventually takes us farther into the solar system than we have ever gone. The building blocks of space infrastructure required to carry humanity on this journey are in development today. At Lockheed Martin, we have a vision for how this future will play out - how each additional piece of infrastructure will build on the next as we explore space, build a lunar economy and settle permanently and sustainably among the stars.

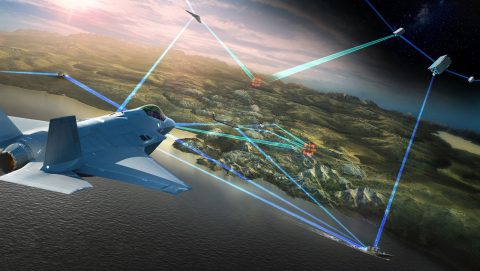

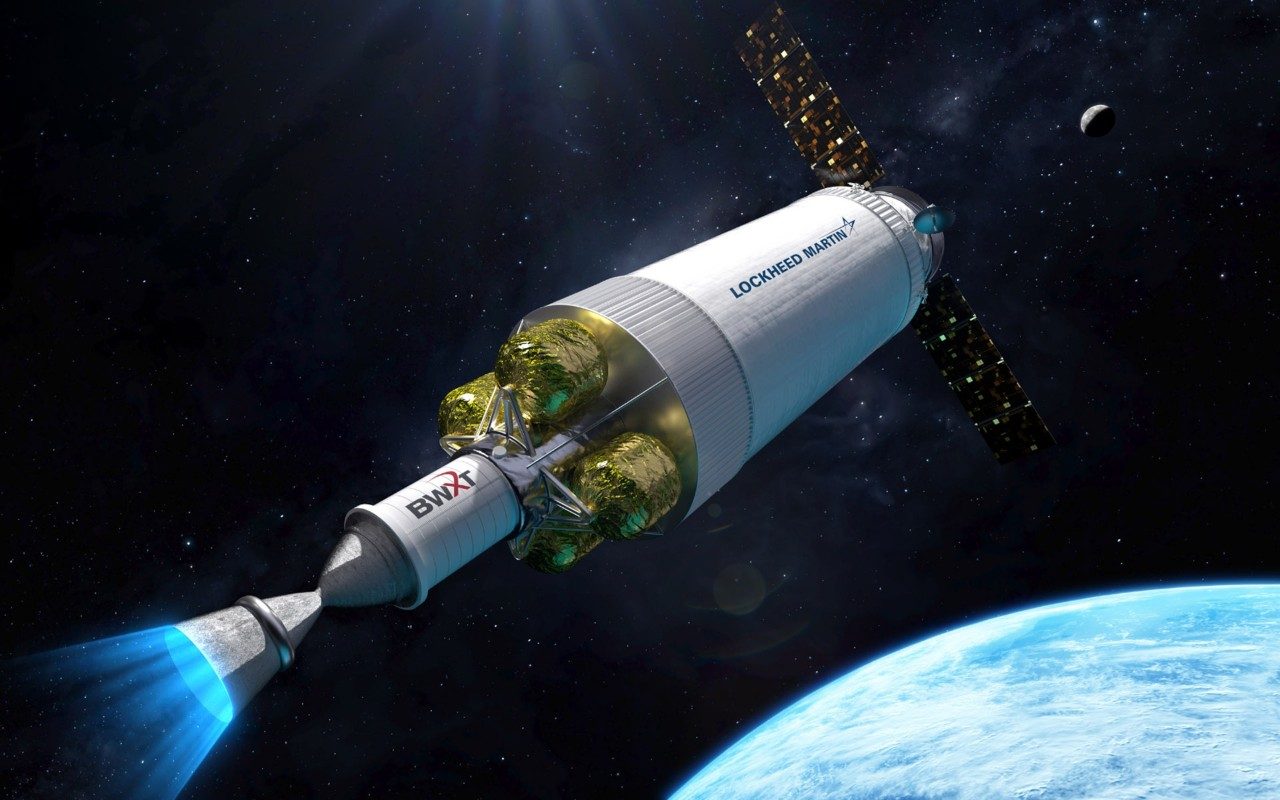

Our approach for a responsible and effective path forward is water-based, nuclear-enabled and commercially-invested.

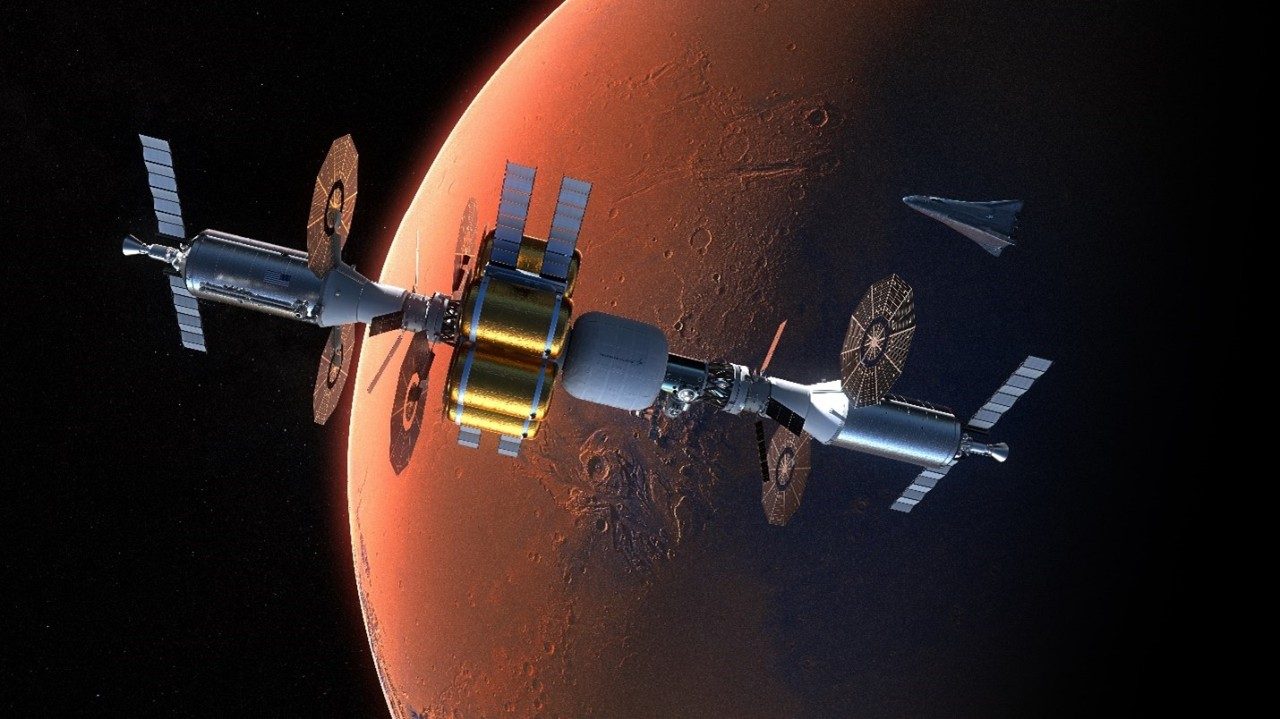

Mars has intrigued humankind for hundreds if not thousands of years. It’s potentially the one place in our solar system beyond Earth that could have harbored life. We’ve been exploring Mars for more than five decades with robots and in the near future, we’ll explore Mars in person. Mars is in our past, it’s in our future and at Lockheed Martin, it’s in our DNA.

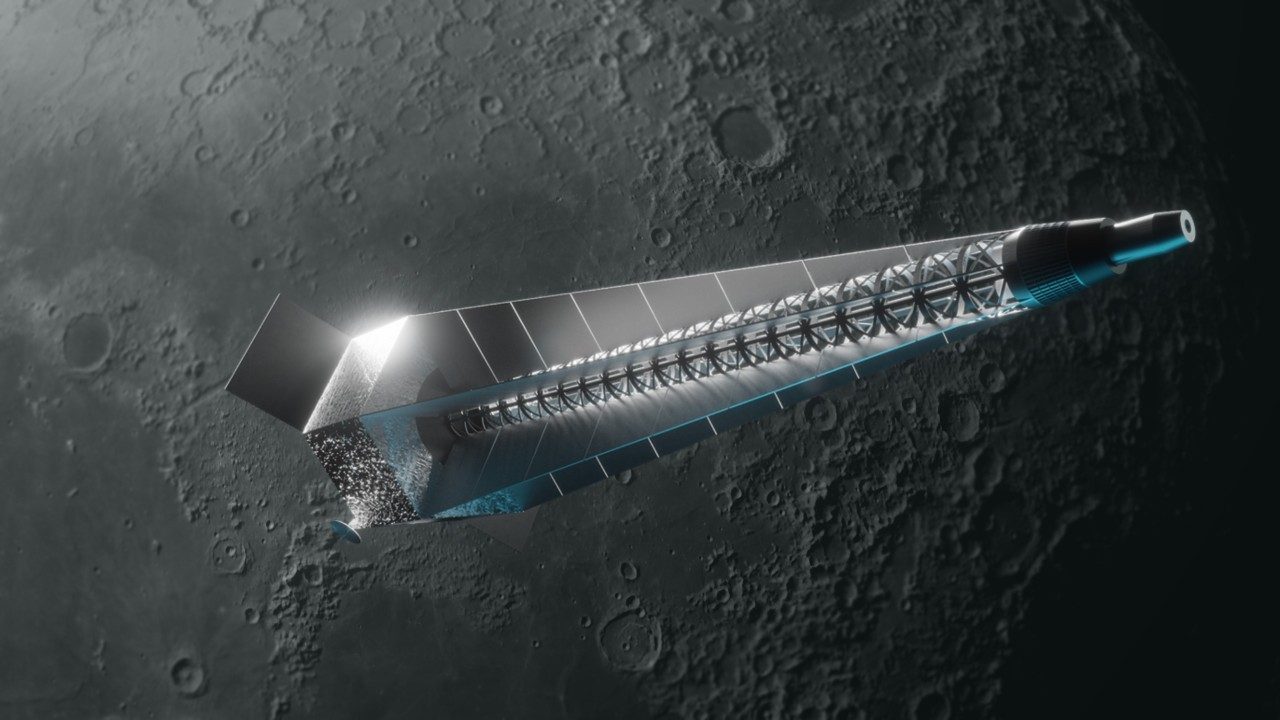

Our conceptual vision for the first interplanetary voyage to Mars is called Mars Base Camp. While in orbit around the Red Planet, Mars Base Camp will provide astronauts a home away from Earth, a platform for conducting critical science and a base to send humans to the surface and back during its three-year mission. Built up at the lunar Gateway, Mars Base Camp leverages the Orion spacecraft, along with nuclear thermal propulsion and inflatable habitation, to enable human space exploration of Mars. A safe and achievable concept, our Mars orbiting outpost is designed to be led by NASA and its international and commercial partners.

.jpg.pc-adaptive.768.medium.jpg)